WASHINGTON — Betsy Devos appeared on Capitol Hill this Thursday to testify about the Department of Education’s proposed budget and Title IX rules that further rethink discipline in the academic setting.

The new budget proposal would change how Title IX, the federal law that prohibits sex discrimination in education programs that receive government funding as well as covers sexual harassment and violence, is applied in school settings.

The proposed rule changes involve new definitions for domestic violence, dating violence and stalking. The changes also include new guidelines for addressing formal complaints of sexual harassment or violence that shift away from what the Department of Education calls the “investigator-only” model and towards live hearings and cross examinations.

Devos also proposed a shift in the burden of proof from a “preponderance of the evidence” to the higher “clear and convincing standard.”

These changes, the Department of Education says, seek to ensure that due process protections are available to all students. The rules are also a response to the increase in reported on-campus assaults during Devos’ tenure.

While victims’ rights advocates welcome the addition of concrete definitions of sexual harassment, some are worried that these rules may make it harder for victims to report and get help after incidents of sexual harassment or violence. Experts also worry about the potential for retraumatization of victims when facing offenders, the high likelihood for a repeat offense, and how the new standard of evidence will dissuade survivors from coming forward.

The proposed rule changes follow on the Department of Education’s move just over one year ago to end an Obama-era push towards restorative justice, which emphasizes repairing the harm of criminal behavior by bringing together all involved parties to discuss the harm done and how it should be resolved. This push had been an effort to reduce the number of disciplined, suspended, and expelled students of color and disabled students, both of whom received disciplinary action at disproportionately high rates.

“We should think of accountability in a less individualized way” said Eve Hanan, Co-Director of the Misdemeanor Clinic at the University of Las Vegas and Co-creator of the University of Baltimore Juvenile Justice Project. “A child in a fight is responsible, but what brought them to that point? What is a school’s accountability? What brings people to the place where breaking the rule is less complicated than the alternative?”

At the time, Devos called the restorative justice a “one-size fits all” solution, and urged schools to “seriously consider partnering with local law enforcement in the training and arming of school personnel” as opposed to using restorative methods to solve conflicts.

Restorative justice initiatives remain popular for those involved in criminal and civil dispute resolution.

“Instead of pulling [offenders] apart from their school community and the people they’ve harmed they have the potential to fix their relationship with their peers, school, family,” said Hanan. “We need to stop trying to exclude or reject people when they commit harm, and instead bring them in closer.”

In participating, victims and offenders are an active part of the resolution of that crime. Victims can decide what is necessary to make up for their experience, and offenders often face reduced punishment.

According to the FBI website, states such as Texas, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Oregon that have implemented restorative justice programs in their schools have seen reduced recidivism rates, improved restitution rates, and over two thirds of victims and offenders reported feeling positive about the process.

The push towards restorative justice also includes an effort to bond communities by teaching both forgiveness and restitution. Restorative justice theorists propose that by rebuilding relationships instead of unilateral punishing wrongdoing, there will be stronger and more cohesive communities and increased social networks within towns and neighborhoods, and therefore less crime in the future.

“Justice isn’t something that happens in one moment,” said urban sociologist Jordana Matlon.

But for sex crimes in particular, some worry that restorative justice is not the right approach.

“Justice reform can have a place to change an atmosphere and move along the sensibilities of someone exhibiting boorish behavior,” said sexual abuse, trafficking, and domestic abuse lawyer Michael Dolce, who himself was a victim of sexual abuse as a child. “But not a behavior that exhibits a kind of pathology like sexual assault.”

The Office of Justice Programs, an agency within the Department of Justice that focuses on crime prevention, reports that sex offenders are often skilled manipulators, a strategy that helps them gain a victim’s trust before an attack. If the same manipulation occurred in a restorative justice setting, it is possible that college administrators wouldn’t notice.

“Can you accept an apology on face value from someone who has the pathology of a sex criminal,” Dolce said, “are you safe now because they made an apology? Or are we reinforcing that from a restorative justice position?”

Prosecutors and police can be satisfied by restorative justice programs because they require the offender to acknowledge guilt and apologize, noted Hanan. But criminal situations can be ambiguous.

“A lot of conflicts that result in harm aren’t as clear cut, there’s a whole world of un-agreed upon facts,” Hanan said. Acknowledging guilt can also mean that the offender has given up his or her right against self incrimination.

Both Devos’ efforts and the efforts of the restorative justice advocates continue as they seek the best way to find appropriate and just solutions for all stakeholders.

“One of the reasons we’re having this discussion is because people are looking for an alternative, some sense of positive outcome for survivors,” said Dolce. “There’s still an opportunity for a sense of justice in lieu of having to gain proof. A victim has an absolute right to confront a perpetrator if it’s right for them, but survivors have different needs in the aftermath.”

But despite the push for a rule shift, some people remain skeptical that justice — either restorative or punitive — can ever be achieved.

“There’s an added level of injustice to expecting justice,” Matlon said. “In the end, justice is contingent on who’s defining it.”

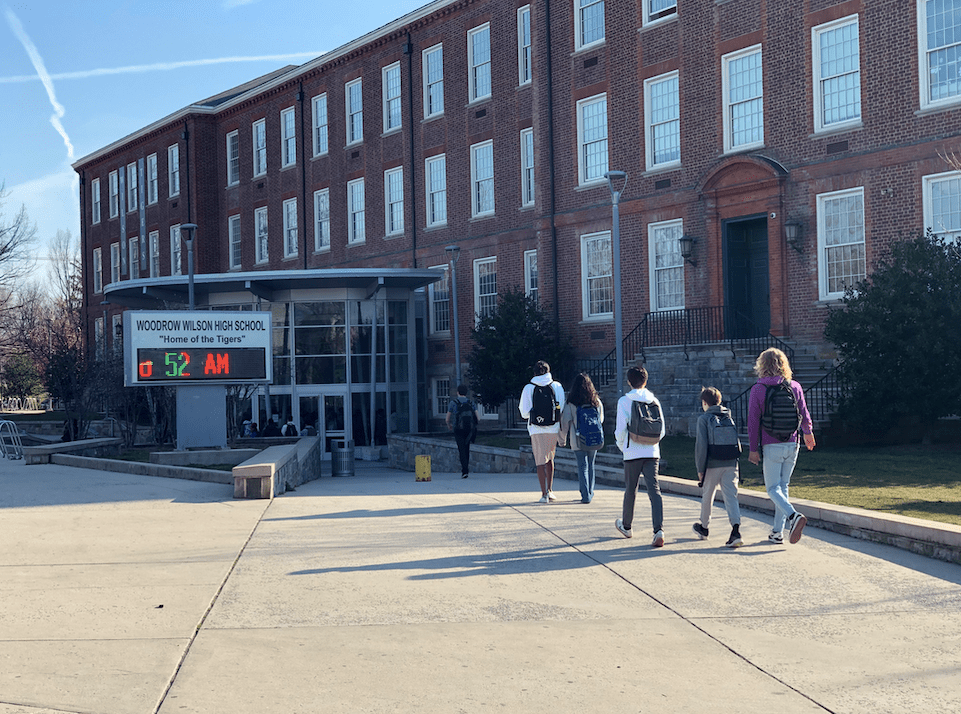

Students enter Woodrow Wilson High School, where the restorative justice program could be affected by Devos’ new proposals. Photo by Hannah Rabinowitz