By Isabella Goodman

Before New York City shut down due to the coronavirus, a normal week for Elenore Simotas included working as an intern at The Bridge, a mental health and substance abuse treatment center where she held multiple group art therapy sessions a day, led individual sessions and did documentation for her own caseload.

Because of the lockdown, she’s learning to navigate the transition from community driven and hands-on sessions to zoom calls. Now, art therapists around the country are tasked with providing meaningful sessions online that produce the same benefits under circumstances they’ve never had to deal with before.

Telehealth, or an online health-related session, is not generally used in art therapy, so art therapists are in a uniquely challenging position to try and provide mental health support to their clients during this pandemic.

“Telehealth isn’t normally used with my population because a lot of them don’t have access to phones and the technology is more challenging,” Simotas said in an interview. Not all the clients have reliable internet service or phones that could support the technology, she said.

“It took a whole extra effort of just navigating like, ‘how do we get people to understand what Zoom is and how do we get them on the computer?’”

Art therapy is a form of therapy that uses creative processes to help heal clients through the process of making art and it helps engage their minds. It’s used with many different populations, from veterans to senior citizens. It’s been used for PTSD, eating disorders, depression, and other mental health-related issues.

With the move online, Simotas also saw the opportunity to help more than just her immediate community. She reworked her website, which was originally just a platform to share her own art, and added an extensive page featuring different lesson plans as well as the option to meet over zoom to go over the directives. She’s currently in her final year of the art therapy graduate program at Antioch University. Because she doesn’t have a license as an art therapist yet, it’s considered art as therapy, not art therapy.

“I made these curriculums already for my groups at work and I was like why don’t I just tweak these a little bit and make them available for other people,” Simotas said.

Though many art therapists are choosing to go completely online, some still have the option of continuing in-person therapy since they’re considered essential workers.

The classification for essential workers differs from state to state, but in Washington D.C., for example, Mayor Muriel Bower issued an order classifying mental health providers as essential.

Clara Keane, who works at the American Art Therapy Association, said in an interview that the organization is trying to provide support with the transition to telehealth as well as those who are having to continue to work in person.

Alison Maples at Embrace Change Therapy in Royal Oak, MI. is continuing to see clients in-person but at an extremely limited capacity. The rest of her caseload has moved online.

“Ninety-nine percent of the clients are online,” Maples said in an interview. “I do have a couple of clients that are in domestic violence situations or clients that are in the LGBTQ community but haven’t come out to their family yet so they don’t feel comfortable being in the house where someone could hear them or people that live alone and this one hour a week is the only human contact they’ve had in a month.”

She’s aware of the risk that comes with meeting in-person and she’s made that clear to her clients as well but is taking all the precautions she can to keep herself and her clients healthy.

“Some still have to go to work in conditions that are not so safe,” Keane said. “If someone’s working in a psychiatric unit, for example, it might be really hard for their residents to follow social distancing guidelines, and if they have to do an art therapy group, they have to be really careful about being hygienic with the art supplies.”

Simotas is not alone in trying to navigate the shift online. It’s something that art therapists across the country are trying to figure out as well while some are learning what it means to be an essential worker.

For art therapists solely doing telehealth, the change was complicated and for many, unprecedented. Art therapists have turned to VSee, Zoom, Google Hangouts, BlueJeans, Prose and others, to varying success.

“Art therapists were a little behind the telehealth bandwagon, because of the hesitance around art supplies and the idea that you can’t be there with them as they make the art,” Keane said.

For Alison Cunningham-Goldberg of Linda Garcia Rose & Associates in New York City, the first goal was to check on the safety of her clients.

“When I first started working remotely, I was very focused on triaging – checking in on people, especially those with depression or anxiety, just to give them some grounding skills,” Cunningham-Goldberg said in an interview. “It was almost like social work.”

Elaina Whittenhall runs the practice Creativity Transforms Therapy out of Austinand began reaching out to her clients at the beginning of April, she said in an interview. Good detail She sent out art kits that would help with coping. The kits differed from client to client, but most featured coloring sheets, watercolors and model magic, as well as a sheet with general tips for coping.

Art therapists realize that not everyone has the same materials available to them. They’ve had had to be resourceful in what they use, whether it’s just a pen and a notebook or an origami project made from a sheet of paper.

In some ways, going online has been a success. Art therapists have had to be collaborative and adaptive but they’re still finding meaningful ways to connect with their clients.

Clarissa Greguska, an art therapist based out of Los Angeles,said that the move online doesn’t necessarily change things because of the already established relationship.

“Regardless of what format were meeting in, there’s still a relationship between us,” Greguska said. “Research shows that the most effective therapy happens when you have a good rapport with your client.”

Simotas has found that the quarantine is eliminating some of the stresses that come with in-person group sessions. She said that a lot of the work she did pre-coronavirus was about maintaining the group space – managing poor boundaries or interruptions. With Zoom, she’s able to mute everyone while they’re creating the art and there’s no way to physically act out.

The transition to telehealth has its challenges, some that affect everyone working from home, and others that are more unique to art therapy.

On top of dealing with the original issues that their clients came to them with, art-therapists are now having to navigate how to help with coronavirus-related stress.

Maples said this is something she and other art therapists are having to face themselves.

“I’m a person too, so I’ve been tired and foggy, a lot of this stuff is weighing heavier on me than it normally would,” Maples said. “And then you get two full weeks of every session or every other session being COVID COVID COVID, it’s been very draining on me as a person.”

Now that things have settled somewhat, Maples says that she’s been able to get back to helping her clients through issues they were working on before the coronavirus.

It’s also been potentially affecting the relationship with her patients, with technology glitches and poor connection becoming a roadblock in the sessions.

Other art therapists agreed, saying that the computer or phone can’t pick up body language the same way and that it’s harder to get to a vulnerable place when the screen keeps freezing.

Some of Whittenhall’s clients are acutely affected by the coronavirus. She has clients that work in the media and can’t avoid the 24-hour news cycles, as well as college students who are unsure of the workforce they’re about to enter into or forced back into homes where they feel unsafe.

Others are losing clients and seeing reduced turnout in group sessions.

“I had one client say ‘I’m on screens absolutely all day with work and meetings,’ she just didn’t want to be on one more screen and she didn’t really want to do the phone so for her, it wasn’t really a replacement for therapy in person,” Cunningham-Goldberg said.

One unexpected problem was the issue of privacy. With everyone working from home, it’s harder to maintain confidentiality with a partner, roommate, or kids in the other room.

“I had to be more intentional about privacy, like making sure my space and my technology is going to respect the client,” Greguska said. “I live with my partner and they’re working remotely so we’ve had to be creative about creating sound barriers but it’s a lot of work to make sure that the privacy is going to be kept.”

There’s also the issue of privacy when it comes to the online platform used for telehealth. Art therapists are having to find HIPPA compliant platforms, but with the mass move to telehealth, some platforms weren’t built for all the traffic and others, like zoom, have previously raised privacy concerns. Because of the coronavirus, the Department of Health and Human Services is relaxing some of the guidelines on what platforms mental health providers can use.

Apart from the issues of running a session online and dealing with these platforms, art therapists are having to navigate trying to navigate licensing problems.

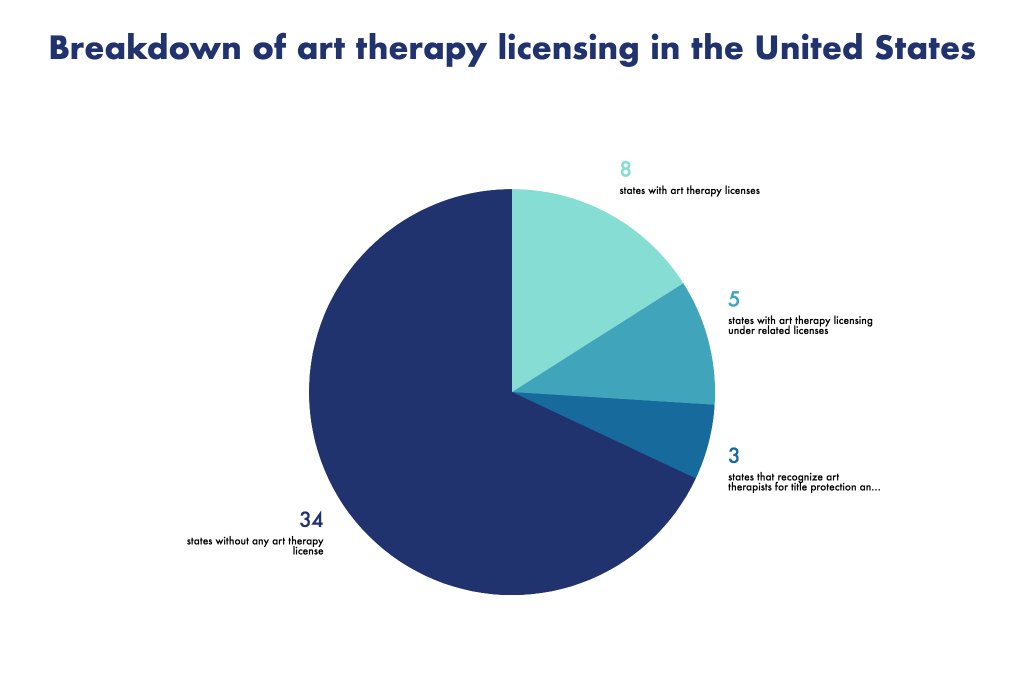

Before the coronavirus, licensing was one of the key issues facing art therapists. Currently, only 16 states have some sort of licensing for art therapists, whether that’s a full art therapy license, art therapy falling under a different license, or recognition for title protection services.

Some see licensing as a way to legitimize the small but growing field. It also makes things easier for clients in terms of insurance. With the move online, some have said that they’re worried about clients who move out state to be with their families – if their home state doesn’t have any art therapy licensing, it can be difficult to provide the help they need.

Now, the push for licensure has completely halted.

“Most advocacy issues that are not directly related to the coronavirus, public health, or crucial state issues have all been stopped,” Keane said. “We’ve had a lot of momentum in our licensure efforts, but it’s paused and we’re not going to be reaching out to lawmakers the way we normally would.”

Keane says that instead, the American Art Therapy Association will be focusing on the conversation around telehealth, mental health and about the benefits of the art-making process. She thinks that the pandemic could potentially change the way that states approach licensure, to eliminate some of the red tape.

This could mean that individuals without licenses, like Simotas could begin to call their work art therapy. Until then, she’ll continue to make lesson plans for art as therapy, in an effort to help people cope.

“I’ve always known that the need was there for art as therapy, just because it’s been so helpful in my life for reflecting,” Simotas said. “People have so much time and they don’t know what to do with it.”