By Ashlyn Peter // May 4, 2020

For almost 10 years, Dr. Julie Hopper watched as her colleagues sailed out to the Pacific ocean each month to collect important scientific data on changes in microbial patterns. The data plays a huge role in determining what kind of funding and policies are needed to protect marine biodiversity, and this study had a lot of it.

But that might not be enough for the study to continue. The study received its funding because it sampled on a regular basis for a long period of time; the coronavirus shutdown in March and April ruined that consistency.

“That is a hole in a scientific study—it’s a gap,” Dr. Hopper, a teaching fellow in the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Southern California, said in a phone interview. “And there’s not supposed to be gaps.”

MISSING RESEARCH

COVID-19 has forced a change in our daily habits and the need to seek out the good when we can during these uncertain times. But as more stories emerge of a healing environment due to the sudden lack of human activity outdoors, scientists worry if this short-term benefit can outweigh the cost of ceased research.

“We’re not in the position to make those predictions because there’s so much unknown right now,” Benjamin Studt, the public outreach supervisor for the Palm Beach County, FL Department of Environmental Resources Management, said in a phone interview. “There is really no telling what could happen.”

As the U.S. classifies what kind of work is and is not necessary during quarantine, scientists worry that they cannot record a momentous time in the nation’s history. “This is the dilemma: a lot of our research work has now been termed a ‘non-essential research activity,’” Dr. Song Liang, an associate professor in the Department of Environmental and Global Health and Emerging Pathogens Institute at the University of Florida, said in a phone interview. “We’re certainly going to lose some unique opportunity to collect data during this time period.”

Some wildlife studies, like the one Dr. Hopper’s colleagues led, are in serious jeopardy of being de-funded as the economy suffers from COVID-19. “Scientific money and funds are hard to come across and now they’ve wasted time and personnel because they had to stop, it was mandated,” Dr. Hopper said. “To me, what actually kind of outweighs any positives on the ocean right now is moreso the negative, the pause, on scientific studies.”

Dr. Hopper believes that any mammals in their mating season would benefit from the decrease in noise pollution, but she says that any surge in offspring would likely only last one generation.

As disconcerting as it is to miss out on valuable ocean wildlife data, marine mammals actually benefit from the absence of research boats: the problem is figuring out which of the two is more important in the long run.

“The manatee population in south Florida has certainly benefited from a decrease in boat traffic,” Studt said. But similar to air pollution, this change may only last until people regain access to life outside the home. “I think benefits to manatees are probably temporary because we live in a boating community and once those boat ramps open up people are going to be back on the water,” Studt said.

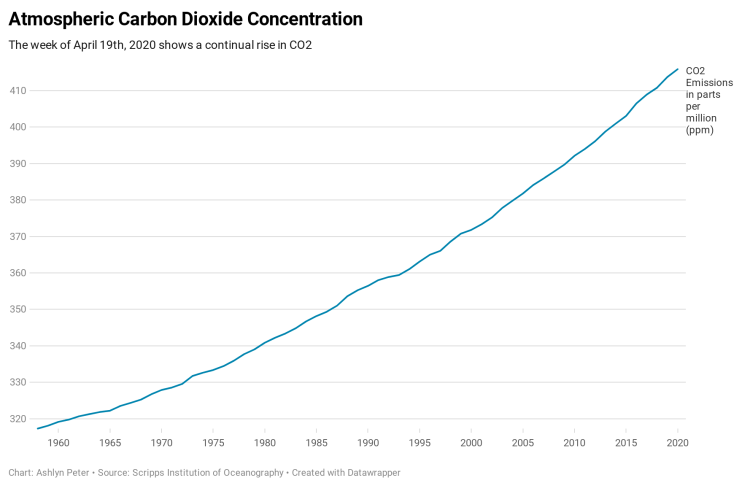

The same tug of war between short-term benefits and long-term consequences exists with air quality. One thing’s for sure, Studt said: with less people driving around, data isn’t needed to know that there will at least be a short-term reduction in air pollution due to the decrease in expended fossil fuels. Still, transportation accounts for the largest carbon dioxide (CO2) contribution in the U.S., so one month of mass quarantine can’t contribute to a long-term solution to air pollution.

MASSIVE SOCIETAL SHIFT

Short-term changes in the environment do not have to be a blip, though. To scientists, a return to business as usual isn’t a given; as interesting as this period of mass isolation is, they’re actually more anxious to know how we move forward from it. Could humans sustain this short-term change in the environment?

Studt is optimistic that we could: as we’ve been forced to stay indoors, many of us have re-discovered our need for nature. “My hope going forward is that people really realize the value of those connections with nature,” Studt said. “We can just hope that the realization hits home and helps us change our habits.”

As most of the public experiences working from home for the first time, some experts wonder whether people will want to continue doing so after stay-at-home orders are lifted. If so, there is potential for real structural change in our relationship with the environment.

“Are people going to be far less interested in traveling through air travel and will people just be happy working at home,” Ronald Amundson, a professor in the Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management at UC Berkeley, asked in a phone interview. “If that’s the case, it’s going to implement a long-term trend in behavior that’s different than the trajectory we’ve been on.”

The question of whether to return to “normal” as we know it has major implications for our environment, as climate change continues to worsen. Permanently changing how and where we do our work would require a massive concerted effort, but many experts have argued that the environment requires an institutional overhaul for years.

“That’s going to be an enormous societal challenge,” Amundson said. “Changes on our behavior will start to shift what we perceive to be the goals of modern life and what kinds of aspirations we should have.”

COVID-19 AS A DIVERSION OR A CAUSE FOR CHANGE

As important as it is to develop environmental policies, Dr. Hopper said it’s also necessary to fight those in place right now. While the country enters into mass isolation for the foreseeable future, the government is deregulating emission levels for companies that emit high amounts of pollution. “Air pollution increases your susceptibility to respiratory diseases,” Hopper said. Since COVID-19 attacks the lungs, “It’s the worst time to deregulate emissions.”

COVID-19 has proved the perfect diversion for the proposals or implementation of these rollbacks, as stories of the illness’ human toll continue to mount. “The focus is on the pandemic,” Dr. Liang said. “Environmental research is just not the priority for now.”

This rollback on emission policies could also deepen the existing healthcare divide for people from low-income and minority communities. The neighborhoods surrounding coal power plants are often majority low-income, which puts an increased strain on an already at-risk population during this pandemic.

Still, scientists are encouraged by the public’s renewed embrace of nature. “It will be interesting how we as a society come out of this,” Amundson said. “This could be a flashing point that scientists and policymakers have been looking for that could be an opportunity to have a conversation and develop policies that help to facilitate behavioral changes that can be sticky enough for people to adopt in large enough numbers.”

Dr. Hopper is encouraged by the news that most gardening websites have experienced backlogs since early March. Learning to care for a milkweed plant or two can be enough to generate a larger concern for nature: it’s an easy habit shift that could lead to future policy changes.

“There’s not much else to do, so I do have high hopes that people are becoming more aware of their natural surroundings and are more interested,” Hopper said. “Maybe even if it’s just a short period of time, people will think, ‘Wow, this is amazing. What can we do to keep it?’”

While Hopper and others agree that better government legislation is necessary for a healthier environment, they also believe that it’s going to take a strong public push to get there. COVID-19 will create a gap in research meant to find solutions to climate change, but perhaps it is also providing a necessary pause for people to reacquaint themselves with nature and the need to protect it.

“At the end of it, it’s really up to us to figure out what happens going forward,” Studt said. “This is a moment for us to take stock of not just ourselves but our interactions with where we live.”