School resource officer Alfred Giusto stands in South Portland High on Friday, March 2, 2018

Photo by Carl D. Walsh/Portland Press Herald via Getty Images.

On her first day as a public school teacher, Hailly Korman walked into her Los Angelas classroom to find there were only enough desks in the room to seat half of the students on her roster. She hurried to the principal’s office to find enough desks to seat her whole class before her students arrived.

Don’t worry, Korman remembers the principal saying. By week two, half of those kids will be gone.

Korman, now an expert on correctional education, justice-involved youth, and school discipline, watched that year for the first time as students fell victim to a discipline system that was meant to keep students safe, but nonetheless left them isolated, pushed them to act out, or removed them from school altogether.

Most students are not even aware of existing mandatory suspension or expulsion laws, which vary from state to state, until they commit an offense — wittingly or unwittingly. According to Korman, when a student commits an offense included in a mandatory suspension or expulsion law, there is a disturbing shift from teachers making individualized behavioral decisions to a legalistic process of protocol and regulation that can leave students stranded.

Fortunate students have parents or advocates who help them either to bypass the punishment or forge a new path completely. Others, most often disabled students or students of color, do not have this support and are left to fend for themselves.

“History has shown that having really hard and fast rules has always managed to be wielded against the most vulnerable,” said Korman. “As much as we’d like to say that there is no discretion here, people with means, people with power, people with money always find their way out.”

A putative approach to school discipline is used with all students, but it is disproportionately used against students of color and students with disabilities who have the least support.

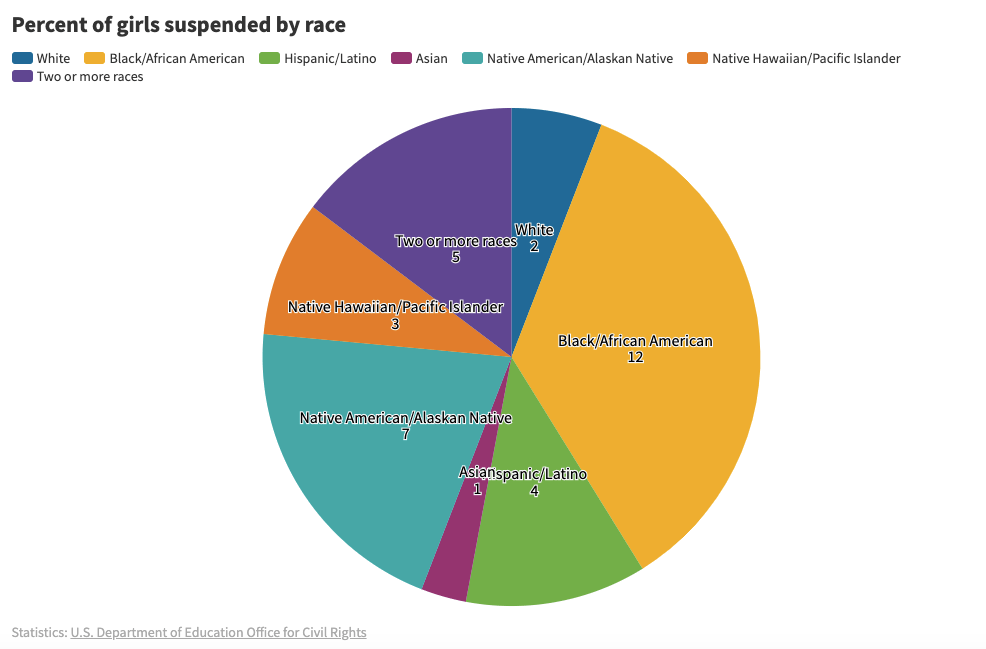

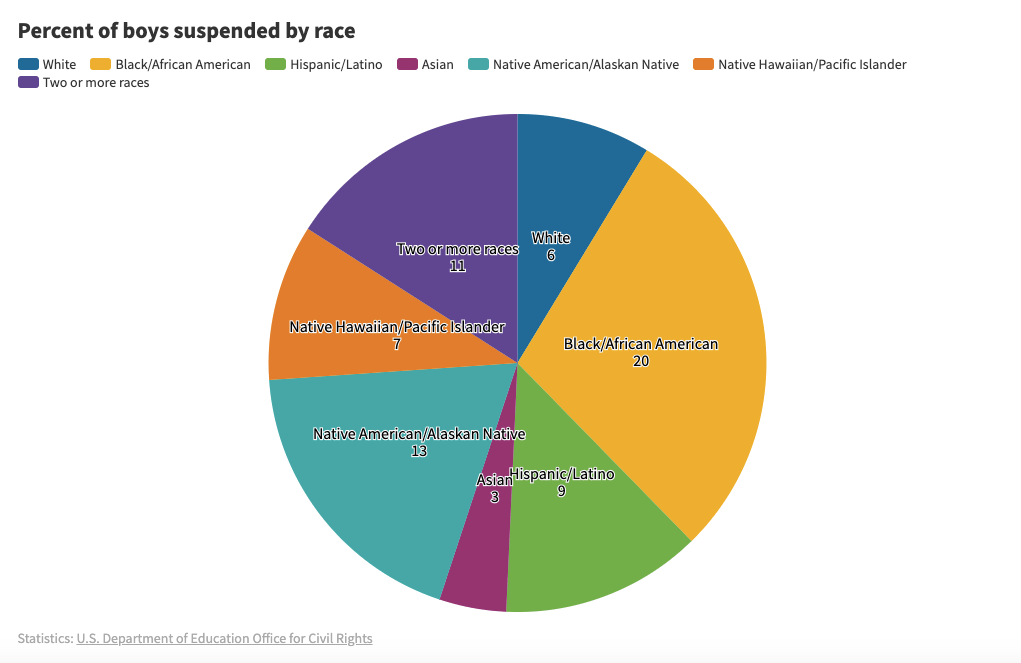

According to the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights, black boys are three times more likely to be suspended than white boys, black girls are six times more likely to be suspended than white girls, and students with disabilities are more than twice as likely to be suspended as their non-disabled peers.

“We have created a chilling environment within the school system.” said Shay Bilchik, founder and Director Emeritus of the Center for Juvenile Justice Reform at Georgetown University. “It’s pushing kids out.”

The U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights also has reported that white students are more likely to face suspension or expulsion for provable offenses, such as smoking or vandalism, while black students are more likely to face consequence for subjective offenses, such as disrespect.

As schools grapple with excessive and disproportionate punishment, educators, federal regulators, and members of the juvenile justice system are increasingly looking to try a new approach which focuses on reconciliation as opposed to punishment, restorative justice. This model requires offenders to take accountability and meet with those impacted by their actions, and together they decide a way to fix what was wronged. Instead of punishment, schools hold a restorative meeting and attempt to cooperatively sort out the issue and improve school culture.

When instituted properly, including specialized faculty training and multi-teared implementation systems to address different levels of transgressions, restorative justice practices are showing some positive results. Suspension rates are dropping, while GPAs, attendance, reading proficiency, and graduation rates all rise. Students and faculty alike report a significant improvement in school culture.

The rise and application of discipline

Even though overall juvenile crime rates are plummeting — the juvenile incarceration rate dropped more than 74 percent between 1996 and 2018 — the number of school disciplinary suspensions are skyrocketing. Out-of-school suspensions have increased by about 10 percent since 2000, and suspensions have more than doubled since the 1970s according to the Southern Poverty Law Center.

Most of these suspensions are a result of zero-tolerance policies, which burgeoned in the 1990s starting with the passage of the Gun-Free Schools Act in 1994. The political rhetoric of the time was primarily focused on crime — gang violence, superpredators, and losing the war on drugs. In an effort to deter violence in schools, the federal government mandated in the Gun-Free Schools Act that any student caught on campus with a weapon was required to be suspended or expelled for one year.

The Gun Free Schools Act allowed for states to develop a case-by-case review process for discipline infractions, which has been widely criticized for its use in non-threatening situations. Students have been held to the suspension mandate for broad interpretations of what constitutes a “weapon.” In Ohio, a 10-year-old boy was suspended for making a gun with his fingers. In Delaware, a 6-year-old boy was suspended for bringing a fork from the Cub Scouts to class. In Maryland, a 7-year-old boy was suspended for chewing a Pop-Tart into the shape of a gun.

Subsequently, almost all states and about two-thirds of school districts developed policies that mandate expulsions for certain infractions, such as using or selling controlled substances, sexual assault, threats, or “any felonious behavior.”

Individual school districts also began to implement new rules based on the broken windows theory — that cracking down on small offenses would discourage serious ones in the future, and would make students feel more safe. This meant that schools were now suspending and expelling students for behavior that previously didn’t warrant it, such as skipping class, insubordination, or being rude to teachers.

According to the American Psychological Association, harsher disciplinary rules do not contribute to an overall safer learning environment. At schools with lower suspension and expulsion rates, academic achievement rises consistently every year, particularly for black students.

“Teenagers misbehave,” said Korman. “The process of adolescence is stepping over boundaries to find out which ones are firm and which ones aren’t. It is the responsibility of adults and communities to give young people safe ways to transgress without catastrophe.”

An increasing amount of school administrators now rely on the police to handle disciplinary action in the form of School Resource Officers (SROs). According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, more schools than ever are hiring SROs to handle behavioral problems.

“As we’ve seen the dramatic rise of police in schools, things have become more police problems than they have school problems,” said Jonathan Scharrer, an expert on addressing racial disparities in the criminal justice system and the Director of the Restorative Justice Project at the University of Wisconsin Law School. “Things have really just transformed from what had historically been handled within schools to getting deferred to police, and become criminal justice responses.”

SROs turn students over to the juvenile justice system even in the case of minor and first offenses, making it easier for students to get a juvenile record and harsher punishment.

“We have a system that’s based on retribution,” said Scharrer. Retribution, Scharrer said, focuses on punishing the accused and does not address any underlying issues. “There’s no response to what’s happened. Instead it permeates and spreads the amount of harm that has occurred.”

When students are forced into the “system,” they are twice as likely to drop out, and over three times more likely to be arrested.

“When we don’t have that appropriate response, we have a very high risk of throwing that child’s life away,” said Bilchik.

The solution isn’t a guarantee

How restorative practices are implemented in schools may dictate their success or failure.

“With any kind of process like this, you gotta do a lot of pre-work,” said Howard Zehr, the founder of modern restorative justice. “You’ve got to talk with people, you’ve got to find out what their concerns are, and help them do a risk benefit analysis and so forth.”

When instituted in the justice system, restorative practices are facilitated by lawyers, psychologists, and experts in restorative justice. In schools, Korman said, it is more often facilitated by educators or counselors without proper training.

“A new behavior program is certainly no harder to do than a new math or reading program,” said Korman, noting that one of the most glaring issues with implementing restorative practices is a lack of teacher capacity. “It does require, though, the investment of building the skills of your teachers. With something around behavior management, typically we’re less inclined to make the investment of time and dollars because we underestimate the dedication of what it takes to do it well.”

Restorative justice specialists like Zehr say that without properly trained faculty, schools will institute programs that do not actually subscribe to the theories that make restorative justice successful in other systems or at the community level.

“One of the problems now is that restorative justice is so popular, everybody’s calling everything restorative justice,” said Zehr. “And so many times you just don’t know whether the program that’s being labeled restorative justice is really restorative justice at all.”

Zehr notes that in the criminal justice world, restorative justice is a voluntary program and consent of the victim is paramount. If it is a mandatory program in schools, this gives the victim no choice but to participate. The experience can be traumatic for the victim, said Zehr, and any outcome could be the result of pressure as opposed to true healing.

Justice-involved youth advocates fear that restorative justice won’t address fundamental issues or needs that may impact a child’s behavior.

“If a child is going off track and is beginning to act out in delinquent ways, it’s usually because there’s things happening in their life that are going off track,” said Bilchik. “For some kids it could be enough all by itself. But I think for others with more complex needs, the response needs to be even more than just the restorative response.”

Some worry that because restorative justice cannot address the underlying causes of bad behavior, it would be a misapplication to consider it a comprehensive strategy to address the high rates of students being pushed into the justice system due to infractions at school, known as the school-to-prison pipeline.

“Restorative justice is not going to meet their [underlying] needs,” said Korman. “Restorative justice does not give you a job, it does not give you a stable home, its does not keep your family safe. Restorative justice on its own is insufficient.”

Restorative practices in schools have not yet been proven to lower arrest and recidivism rates for students. This has provoked additional backlash against its legitimacy. Experts argue that the practice is about more than recidivism, and shouldn’t be graded on that alone.

“A lot of things that we hope to accomplish are not measures that the system cares at all about,” said Zehr. “They honestly don’t care about victim’s satisfaction, or those kind of things. Reducing recidivism is absolutely not the goal. It’s a benefit. A side effect. But in my view, it is absolutely not a primary goal of restorative justice.”

Critics call restorative justice a lax response to bad behavior which could lead to disastrous effects.

Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos and White House officials have both said that Obama-era restorative justice guidance led to more lenient consequences, and therefore made schools more dangerous, pointing to the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School as a costly example. The Broward County school district, of which Marjory Stoneman Douglas is a part, was one of the first to implement restorative discipline practices. Nikolas Cruz, who carried out one of the worst school shootings in U.S. history, was often reported for violent and disruptive behavior according to school administrators, but was never expelled. While it’s not clear if Cruz participated in the restorative program, some blame the school’s alleged leniency for allowing a shooter to slip through the cracks.

Restitution

There is a growing consensus that implementing restorative justice versus punitive justice practices in schools should not be an either/or approach. Advocates say there is a way to preserve the learning time of a class and protect and engage the students who misbehave equitably.

Schools who are doing this well have established clear restorative guidelines to improve school culture and build relationships while simultaneously training teachers in replacement discipline strategies and behavior management techniques. At the same time, they’ve backstopped this new approach by establishing strict guidelines for discretionary suspension or expulsion when necessary.

“We have a system design in which school leaders are allowed, maybe encouraged, to abdicate responsibility for students learning the moment they are outside the door, even though there is no one on the other end to pick up the responsibility,” said Korman. “There is no such thing as ‘going too far’ when trying to keep kids in school. That’s an ambitious principle, but I think we’re up to the task.”