When the coronavirus pandemic hit Washington, D.C., Mason Ferguson, an American University student and part time nanny from Colorado, wasn’t sure what she would have to do.

She started nannying for Hilary Foster, a new working mother Washington, D.C., in January. She cared for Foster’s baby 30 hours per week while a full-time student at American University studying justice and law.

“I wasn’t sure if my nannying job would still be on,” Ferguson said. She lived on campus, which got shut down after classes moved online in March, so her housing situation was uncertain too.

Many domestic workers — the name for a broad category of both essential and non-essential workers like nannies, house cleaners, home health care aides, au pairs, gardeners, and more — have faced similar or even greater uncertainty since the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic.

The Economic Policy Institute estimates that there are 2.2 million domestic workers around the country, many of whom are now out of work. Ferguson is one of the more than 200,000 nannies across the United States, according to EPI numbers.

They usually come from vulnerable positions in society — more than 50 percent live near or below the poverty line and more than 90 percent are women, disproportionately women of color and immigrants, according to EPI.

Domestic employees are a class of workers who, from the beginning, have had very few workplace protections. Childcare workers are among the lowest paid occupations nationwide, with a median wage of less than $12 per hour.

According to the National Domestic Workers Alliance, many domestic workers work with no labor protections whatsoever. A lot of domestic workers work without any sort of written or verbal contract. They get no paid sick leave or time off.

Until recently, they could not access unemployment benefits, since they are considered independent contractors like rideshare drivers and freelance writers. Now, citizen or legal resident domestic workers can access these benefits, however a large portion of domestic workers are undocumented.

According to EPI, at least one in five domestic workers nationwide are undocumented. In D.C. and other large cities, that rate is likely far higher, according to Rocío Ávila, state policy director for NDWA.

In some parts of the Washington region, like Langley Park, Maryland, as much as 70 percent of adults are not U.S. citizens.

Because of the unregulated and informal status of domestic work, it is almost impossible to say what portion might be undocumented workers, Ávila said. What is clear, she explained, is that domestic workers across the board, but especially undocumented domestic workers, are hurting badly right now.

In a recently released survey of more than 16,000 domestic workers, NDWA said that 72 percent reported having no jobs for the week of April 6. Seventy percent say they don’t know if they’ll have a job again after the pandemic passes.

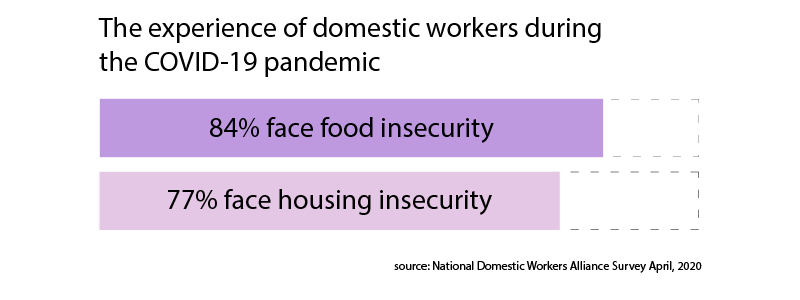

Nearly 80 percent of surveyed domestic workers are their household’s primary breadwinner, according to NDWA’s survey results. Most are now facing food and housing insecurity — 84 percent and 77 percent, respectively.

“I have already lost the majority of my cleaning jobs and am now having to face how I will pay my rent or even pay for food,” said Ingrid Vaca, a D.C. domestic worker and organizer with NDWA in a press release.

For Ferguson, the stakes weren’t that high. She would have been able to feed herself no matter what. However, the virus has still had a dramatic impact on the course of her life.

“I was really trying not to go back to Colorado,” Ferguson said. “My mom is a nurse and is working the frontlines right now and I really didn’t want to go back home for that reason.”

She was left with a difficult choice — she could either go back to Colorado or stay in D.C. by herself facing all the uncertainty of the weeks ahead alone.

Foster was away when outbreaks started occurring around the country.

“We were out of town on the very last bit of my maternity leave, when the whole COVID thing really started happening and the shutdowns became clear,” Foster said.

Her family was in a tricky position too. She and her husband had to start working their demanding jobs from home, something she said she was thankful they had the ability to do, but would nevertheless be difficult with a newborn.

Her other part-time nannies went to work full-time for other families during the pandemic. Luckily, Ferguson needed a place to stay and a way to keep earning money through the pandemic.

“We were left with the option of having Mason work more hours, which has been really amazing,” Foster said. “And we’ve brought her in to be part of our quarantine family.”

Many domestic workers have been put in a similar situation with their employers, faced with the choice to move in or lose work.

For Foster and Ferguson, it worked out in a mutually beneficial way. Ferguson was able to stay in D.C., have people to stay with to not be completely isolated, keep earning money, and have room and board. Foster can keep working full-time and know her son has someone to interact with and is being cared for.

For many domestic workers this situation could simply never work out, according to Rocío Ávila, state policy director for the National Domestic Workers Alliance.

Many are parents themselves. Many have older or younger relatives to look after at home.

Ferguson, in contrast, has her food and rent taken care of now that she is living full-time with the Fosters. She is earning more money than she did before, as she now works 40 instead of 30 hours per week and time-and-a-half if she works overtime. The coronavirus pandemic has still significantly changed her life and thrown plans off course, but she said she is lucky to not be burdened by rent and food costs on top of a loss of her job.

Had she lost her job, her status as a U.S. citizen would still give her advantages over many others in her field. Undocumented workers will receive no federal coronavirus relief assistance and little state or municipal assistance, according to Ávila.

The D.C. Council considered a package that included two programs with a total cost of $75 million to support people left behind by unemployment insurance. However, that part of the package did not pass, generating controversy among members of the council on a Zoom call.

While the Council did not pass the measures, they are providing some relief for undocumented workers through the public-private partnership organization Events DC.

The $18 million package distributed through Events DC will contain $5 million in relief funds for D.C.’s undocumented workers.

While, Ávila was glad the council passed any relief measures for undocumented workers at all, she said $5 million was completely inadequate — 1/15th their original ask. With more than 20,000 undocumented workers in D.C. alone, this program would only provide a one-time payment of about $200, Ávila said.

NDWA and others are working to fill the gaps.

The Northern Virginia Family Service, which runs a variety of programs from child care service to food pantries, is providing small grants to cover specific expenses like rent, groceries or other bills, said David Billotti, a spokesman for the century-old agency.

People can fill out an application and provide documentation of their specific coronavirus-related need, and the agency will write a check for the full amount to the person or company they owe.

Billotti said they have seen applications for this and use of NVFS’s other services, especially its food pantry have skyrocketed since the pandemic began. He said their funds are limited, but they are happy to help with emergency payments, food and more.

NDWA has raised $4 million in its Coronavirus Care Fund, which will distribute $400 to 10,000 domestic workers, a number Ávila said was derived from the statistic that 40 percent of Americans cannot afford a $400 emergency.

However, we are currently in an emergency that is costing everyone far more than $400, she said. As most states go into their seventh week under stay-at-home orders issued by their governors, many have lost nearly two months worth of income while still paying rent and putting food on the table, or accruing debt from those expenses.

Foster said she has an idea of the struggle many domestic workers are going through, which is why she has continued to pay the bi-weekly cleaners who used to come to her house but can no longer work because of the virus.

However, many domestic workers have less scrupulous and ethically minded employers, who may not even be maintaining contact let alone payments, Ávila said.

“They’ve been super accommodating,” Ferguson said, explaining that she is now in finals week at school and is recovering from a hip surgery, which means she has to go to physical therapy twice a week.

“I wanted to be very clear from the beginning that her health is the most important thing, so, of course, we’ll be flexible around that,” Foster said.

“I haven’t asked for any more time off, but I know if I were to that they would work with me,” Ferguson said, adding that the Fosters understand school is her first priority.

“Because Mason is a full time student, we want to make sure that she has enough time for the most important thing, which is her studies,” Foster said.

Ferguson now has her own space in the basement apartment below Foster’s home. She shares meals and living space with the family as they batten down the hatches to weather the coronavirus pandemic.

“It’s sort of more intimate than I had imagined,” Foster said. “But she’s really wonderful and it makes me really happy that my son can have more people than just the two of us to interact with.”

“I’m extraordinarily lucky that we have childcare at this point, and it’s a fantastic person,” Foster said.