These are just some of the music streaming apps that will be impacted by the Music Modernization Act. The MMA will create a database for streaming apps to distribute royalties better and give federal copyright protects to songs released before 1972. (Photo by Alexandra Kerecman)

By Alexandra Kerecman

WASHINGTON – Almost two years ago, President Donald Trump, with Kid Rock by his side, signed an unanimous bill into law that will bring dramatic change to the music industry when it goes into effect in 2021. However, not many people outside the music industry have heard of the Orrin G. Hatch-Bob Goodlatte Music Modernization Act.

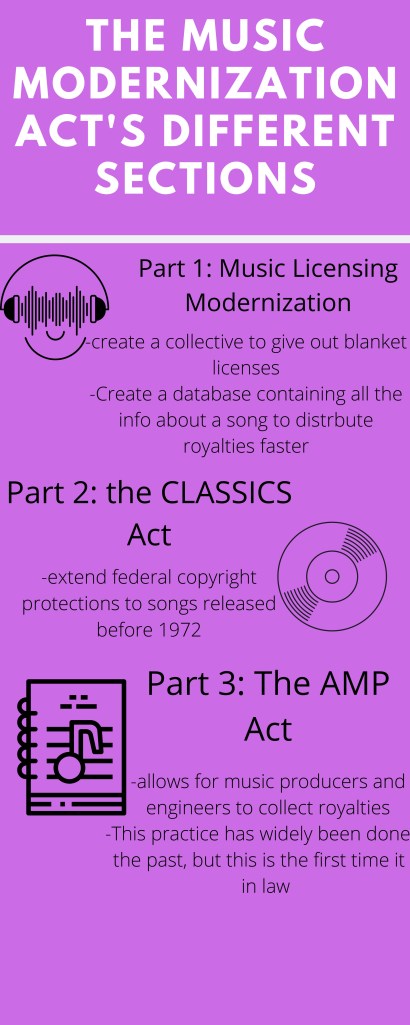

The Music Modernization Act, passed in 2018, requires that a government-funded commission be created to deal with licensing and royalties, gives federal copyright protection for songs release before 1972 and allows for music producers to collect royalties if a recording artist declares that they were a key part to the song recording.

“The MMA is a bunch of different things that were all put together in one bill,” said Todd Dupler, the managing director of advocacy and public policy for the Recording Academy, in an interview. “There are elements of that bill that have been out there for years. In fact, a version of the law that deals with the Mechanical Licensing Collective had been proposed 10 years prior, going back to 2006.”

The first part of the Music Modernization Act is called the music-licensing modernization. This section will allow for artists to receive more royalties from digital streaming services, like Spotify and Apple Music, that they might not have before due to inefficient record-keeping of who owns the copyrights to songs.

The Mechanical Licensing Collective is comprised of songwriters, music publishers, and other people involved in the industry. Ralph Peer’s company Peermusic, a global music publishing group, is one of 16 organizations on the collective’s board of directors. This group will give blanket licenses to services like Spotify and advocate for fairer compensation for all parties involved.

The new act replaces individual licenses with ones that allow for a streaming platform to play all compositions from a music publisher that the streaming platforms have an agreement with. This type of license would replace the outdated mechanical license where a streaming service most have one for every song they have. For instance, if Spotify had about 10,000 songs from the same music publisher, they would need 10,000 mechanical licenses from that publisher for each individual song.

“Peermusic, which is a fairly large independent, probably has over 100,000 different songs that are used on streaming services,” said Ralph Peer, the Chair and CEO of Peermusic, in an interview. “You are in six figures for the number of licenses a smaller publisher has and seven figures as soon as you get to the majors.”

According to John Simson, an entertainment lawyer and former executive director of SoundExchange, an organization that helped distribute royalty payments from streaming services to music publishers, the average amount made off a physical or digital purchase of a song is 91 cents, but the average amount made per stream ranges from three-thousandths to six-thousandths of a cent depending on the streaming service.

The Music Modernization Act requires music publishers, streaming services and the United States Copyright Royalty Board to work together to create a new amount that is agreed upon by all parties.

The second part of the Mechanical Licensing Commission is to create a database using information from music publishers and songwriters to identify where royalties made from streaming services would go to. While the amount made from streaming a song is around three-thousandths of a cent, there are thousands of songs that do not have anyone listed as an owner but are still making money that is sitting unclaimed. This database hopes to get the unclaimed money into the hands of a song’s owner and make royalties available to all songwriters and publishers faster.

However, there are some songs that have widely known owners but are being declared as unclaimed, so these songwriters and publishing companies are not getting royalty payments from streaming services. Streaming services claim it is too hard to keep proper track of licensing paperwork at the moment, which causes for the licenses of some songs to fall through the cracks. The most prominent example of this is Eminem’s publisher suing Spotify because Spotify used Eminem’s songs without the proper licensing and did not pay royalties because the streaming service did not know who the proper owners of the songs.

This lawsuit may even reach the Supreme Court because Eminem’s publishers are claiming that the Mechanical Licensing Commission part of the Music Modernization Act is unconstitutional and prohibits the right to sue. There is a provision in the Music Modernization Act that bans publishers or songwriters from filing a lawsuit against streaming services for unclaimed royalties after January 1, 2018. While this case is still in litigation, a federal judge in Nashville denied that the lawsuit should be moved to New York to make it easier for Spotify to defend itself.

However, Simpson believes this lawsuit will probably not make it far.

“For you to tell somebody that they are not allowed to sue is probably problematic, but if the way you do it is to say look we are changing elements of the statutory license that is required by Congress and Congress has the authority to change the terms of the statute,” said Simson in an interview. “The MMA did this.”

The second part of the Music Modernization Act extends federal copyright protections to songs that were released before 1972. Songs released before 1972 were not given protection on the federal level, so artists had to depend on the copyright laws of the state they lived in to protect their songs. The money made from these streams may help artists who can no longer tour due to age.

Due to the recent COVID-19 quarantine, the Music Modernization Act may help these older artists get more money from this act due to an increase in the streaming of catalog music as the quarantine continues. Catalog music is any piece of music that has not been released in the past 18 months.

“A lot of catalog music is being played right now as people are at home in quarantine,” Dupler said. “People are kind of looking for comfort music and they go back to the oldies. This is music that artists should be paid for.”

The last part of the Music Modernization Act is a rare inclusion that allows music producers or engineers to collect royalties from songs if they are given permission by a recording artist or music publisher. While this practice has been in place for some time, this is the first time it has been written into law.

“It codifies a practice that has been in place for years, but producers and engineers have never been acknowledged or recognized in copyright law,” Dupler said. “This gives them something in the law that recognizes them for the work that they do. Even that alone is a very important and powerful thing.”

The biggest take away from the Music Modernization Act is the ability to see what the music industry can accomplish when music publishers and streaming services work together. This act passed in unanimously in Congress with the help of both sides of a fractured industry coming together to make the industry a better place.

“This (act) takes away an important source of friction between the publishers or composer’s biggest clients and these large firms that are big enough to trample us at any time they want,” Peer said. “To take that friction away is a very good thing for all of the music community.”

It is rare for the music industry and streaming services to work together due to the notion of how much a songwriter or publisher should get paid from having a song streamed. While the average amount of receiving about a three-thousandths of stream does not seem a lot, the Music Modernization Act has opened a forum of communication between streaming services and other players to the industry to make it a somewhat even playing field.

“I think the biggest triumph of the MMA is that it shows what we can do when everybody in the music industry works together,” Dupler said.

“The act is an important step forward to changing the licensing of compositions for on-demand streaming services to mirror business practices and make it fairer for everyone involved,” Simson said.

Getting different sides of the music industry to work together taught the power of unity when trying to pass legislation. The unanimous passage of the Music Modernization Act may inspire factions of the music industry to work together again to pursue more positive legislation.

“It did not happen easily to get a unanimous vote, but I think it has a couple of lessons,” Dupler said. “One, we are better when we all work together; and two, that creators have a voice. When creators realize they have a voice and we can advocate on their behalf, that is when a lot of things can happen.”

“Things like this (the MMA) take a while for new laws to get into place, but things like this are pretty promising,” Andy Valenti, a guitarist and singer for the DC indie soul band Oh He Dead, said in an interview. “The music industry, in general, needs serious innovation right now because people cannot rely on live shows. The Music Modernization Act helps entertainers and performers to find ways to make more money while putting their art online.”